19 min read

Outrageous Conversations: How to convert controversy into connection

Alicia McKay

Jul 11, 2022 1:05:20 PM

Alicia McKay

Jul 11, 2022 1:05:20 PM

Thank you to everyone who contributed to this article. Your thoughts, links, resources and ideas were invaluable in pulling this piece together. I've captured many of your musings in the output below, but you can find a summary of responses at the bottom.

Use the links below to work your way through, or read at your leisure.

- Do we have an outrage culture?

- Should leaders be engaging in controversy?

- Why is it so hard to have these conversations?

- What are the ingredients for productive conversations?

- How can you tell if it's worth engaging?

- What process should you follow to make progress?

- Why should I have to?

- Your thoughts and ideas

We live in outrageous times

Maya Angelou said, “Each time a woman stands up for herself, without knowing it - possibly without claiming it, she stands up for all women.”

She’s right, of course. But man, I’m tired. The pressure of being an unelected and unskilled feminist representative makes it hard to do the job well. I don’t always describe issues properly. I sometimes get hurt and frustrated too quickly, and instead of directing my annoyance at the patriarchy, I turn my resentment and disappointment inward or unleash it on others. It’s exhausting.

Feminist or not, there are many things to be outraged about. Roe v Wade. War in Ukraine. Climate inaction. Child poverty. Economic uncertainty. Racial discrimination. Housing affordability. Income inequality. Political corruption. Gender discrimination. Insert cause here.

If you’ve logged into social media recently, you could be forgiven for thinking people are more outraged than ever.

Are we losing the capacity to come together on conflicting views and ideas?

Are we all just preaching to the converted, deriding the opposition and doing nothing to spread understanding?

Maybe.

But surely the answer isn’t to put the anger away – minimising struggle only makes it less visible. So, what do we do when we’re full of valid moral outrage?

How do we connect with people who think differently and have constructive dialogue without despairing at their ignorance, inadequacy, or demonising their views?

In this article, I will unpick what's driving our outrage, how to show up with confidence and provide a step-by-step guide to tricky conversations.

Social media fuels unproductive outrage

Like anything at the intersection of personal feelings and the Wild West of the internet, our perception of outrage is out of proportion. According to experts, we’re no more outraged than ever – but what we’re outraged about and how we express that outrage is different.

Mark Manson argues, “It isn’t that our beliefs have changed; it’s how we feel about the people we disagree with.” He blames the internet and personalised content algorithms for reinforcing existing beliefs over promoting tolerance. This argument has real merit in the age of clickbait and keyboard warriors, where people consume news through social feeds rather than papers. Manson believes we're more conscious of big-picture issues but are more intolerant of each other and opposing viewpoints.

Social media has a lot to answer for. In some fascinating research on social media outrage, Vedanta and Bavel found that every moral or emotional word used in a post (like abuse, kill, shame, sin, hero, hate, faith or evil) increased sharing by 15-20%. Those shares are served to people with existing opinions - both for and against, stoking existing viewpoints into a frenzy.

It's addictive, too. While I’m not totally convinced by Dr. David Brin’s theory that we’re "addicted to self-righteousness”, I’m unsurprised to learn that expressing moral outrage online earns us positive social feedback, thereby increasing the likelihood of future outbursts.

All of this research confirms what you instinctively know: anger drives engagement. The real worry is about who it’s engaging and the effect it’s having. Are we changing people’s minds or reinforcing existing beliefs more deeply?

The data supports the latter, though the magnitude of the effect varies depending on the platform you prefer. Places that give you more autonomy over your feed, such as Reddit, are less culpable in creating echo chambers. In contrast, algorithm-driven platforms such as Facebook and Twitter drive people deeper into polarised pockets of outrage reinforced by a community of like-minded peers. We're not learning from each other, we're becoming more certain about what divides us.

Leaders need to lean in to outrage

You could be forgiven for throwing your hands up in despair. I do this often. Why wade into the controversy only to leave feeling frustrated? Who’s going to listen? Scroll on by and keep your thoughts to yourself. Rocking the boat on the internet, at drinks or in the office is not an instinctive or rewarded behaviour, and most prefer to avoid conflict.

This is a problem. When people with a voice stay silent, we leave the most affected groups with the job of educating and advocating for themselves. Our silence minimises struggle and places the burden for change on the most burdened among us.

As Jess Berentson-Shaw of The Workshop so eloquently puts it in her webinar on inclusive city design “We can’t ask people who are the most harmed by our current systems and structures… to simply change their behaviour or make better choices. That’s simply not right, and the research tells us that it’s not particularly effective either… What we can do is create an enabling environment.”

Leaders create enabling environments with space for productive discussion.

When we have social, political or community power, we must be literate in controversy. We must know how and when to engage usefully. When leaders choose not to engage in conversations on contentious topics, they create an environment that suppresses useful debate and, ultimately, perpetuates inequality.

Leaders need these conversation skills to drive fair outcomes and progress, whether it’s at work or in their communities.

We're programmed to avoid conflict

There’s a very good reason we avoid controversial conversations: they’re hard! They have lots of feelings and trigger intense emotions—trauma, defensiveness, and personal and political angst. These are tough feelings for even the strongest of relationships to withstand. Professional connections and strangers on the internet barely stand a chance.

We’re programmed to avoid conflict and lack the emotional literacy to navigate such choppy waters. These aren’t the skills we learn at school, university, or home. Even if we did, those skills would be of little use online, where many conversations occur. The freedom of perceived anonymity unleashes the darkest and most combative human urges – anyone who’s ever scrolled a comment thread in perverse fascination will have seen how quickly it all goes south.

Worse, we’re not half as rational as we think we are. We’re walking bags of hormones, values, fears and feelings, with an astonishing ability to post-rationalise, convincing ourselves we came to logical conclusions rather than impulsive instincts. It’s why logical appeals are rarely effective: you can’t change feelings with facts.

Talking about tricky stuff doesn't come naturally, regardless of which side of an argument you’re on. We’re physiologically programmed to defend our own points of view – there’s even a word for it: ‘reactance’. We cling to the anchoring comfort of our convictions because they help us make sense of the world around us. When we share our opinions with others, we hold them closer still, a survival instinct that keeps us safe. Historically speaking, disloyalty is dangerous.

Your personal style of problematic communication will vary - maybe you stay quiet and wait for things to blow over. Maybe you storm off in a frustrated rage. Maybe you get personal and mean. Maybe you get emotional and cry. Maybe you don't engage at all. Maybe you become condescending and state your ideas as though they're facts. Maybe you're one of the unicorns that does none of those things.

Overcoming this programming takes real intention and effort. Below, I've outlined five key ingredients to check off before entering any difficult chat to manually override your default settings.

Five ingredients for productive conversations

There are five key ingredients for having outrageous conversations that result in progress.

.png?width=500&name=PERSPECTIVE%20(1).png)

1. Positive intent

If you can’t assume positive intent from your conversation partner, you shouldn’t have the conversation. Otherwise, it will be difficult to avoid contempt when you feel challenged—this one is particularly hard for me. Contempt is a dark internal fear that creates deep external wounds. Once you roll your eyes, become sarcastic, or use personal insults, your connection is poisoned.

Check your own intentions, too, to make sure they're positive. If you’re entering the chat to make someone feel small or silly or to make yourself feel better... don't.

2. Perspective

Conversations that connect focus on problems, not people. When we lose perspective and allow things to get personal, we become defensive—and fair enough. That's not what you signed up for. Productive conversations can stay in the ‘ideas’ zone, steering away from language and suggestions that this is a personal matter.

People love to be right. Remember that we’re not trying to persuade people, we’re trying to debunk ideas that don’t serve any of us and find new ways to be right together. This only happens if we focus on the idea, not the person.

3. Possibility

Be open to changing your own mind. Some of your convictions are definitely wrong, incomplete or biased. If you can't be open, neither can anyone else.

Recognise that we’re all prone to cognitive biases that make it hard to absorb information objectively and allow for that in your assessment of yourself and others.

These include:

-

Cognitive dissonance: We would rather deny new information that makes us uncomfortable than change our worldview to accommodate it

-

Sunk cost bias: If we’re already publicly committed to an idea, we’re less inclined to change our thoughts. We view our previous thoughts and choices through rose-coloured glasses.

-

Dunning-Kruger effect: The less detail and nuance we understand, the more confident we can be in the validity of our own opinion.

-

The backlash effect: When we start to doubt our position, we often double down on it.

You can't remove these, but you can know when they rear their ugly head and call them out.

4. Precaution

Don’t enter a conversation that has no chance of going well unless you absolutely have to. Spend time gathering your thoughts before entering the mire of controversy, getting ready for difficulty.

Then, once you’re there, remember WHY you’re there. It’s easy to get stuck in a trap of trying to persuade and no longer listening. When people describe their experiences to you, respect that by believing them. When others are speaking, it is not the time to focus on preparing your response. Absorb.

5. Pragmatism

You aren’t going to transform someone’s mindset in one conversation. For this reason, it’s important to be practical about how far you will nudge the dial.

I like resources like the Kubler-Ross change curve, and the Intercultural Mindset continuum for diagnosing how ‘ready’ someone is to change their mind, and how open and informed they might be on a given issue.

Check out both of these resources—or take a look at the tool below to help you make the call. The better the conditions, the more likely you are to make real progress.

Conversation conditions

%20(1).png?width=800&name=PERSPECTIVE%20(800%20%C3%97%20500%20px)%20(1).png)

The red zone

If you're in the red zone, seriously consider avoiding conversation. You're unlikely to encounter openness, with low odds of brokering peace and tolerance. You will come out feeling worse than you went in. Step away.

The orange zone

The orange zone might be characterised by universalism and difference-washing. These behaviours present as a meritocracy, oblivious privilege, or statements like "I'm blind to gender/ colour/ race", "I think we're all the same/ everyone is equal", or "Why should anyone get special treatment?" In this case, consider engaging—not for change but to surface some of the complexities the other person may not have considered.

The green zone

If you're in the green zone, you've got real scope for asking good questions, digging into differences and engaging in mutual reflection and change - so make sure you do the conversation justice by staying as open as you'd like the other person to be.

Once you've got a handle on the conditions, you can prepare for your conversation, using your conditions assessment to inform the go/no-go.

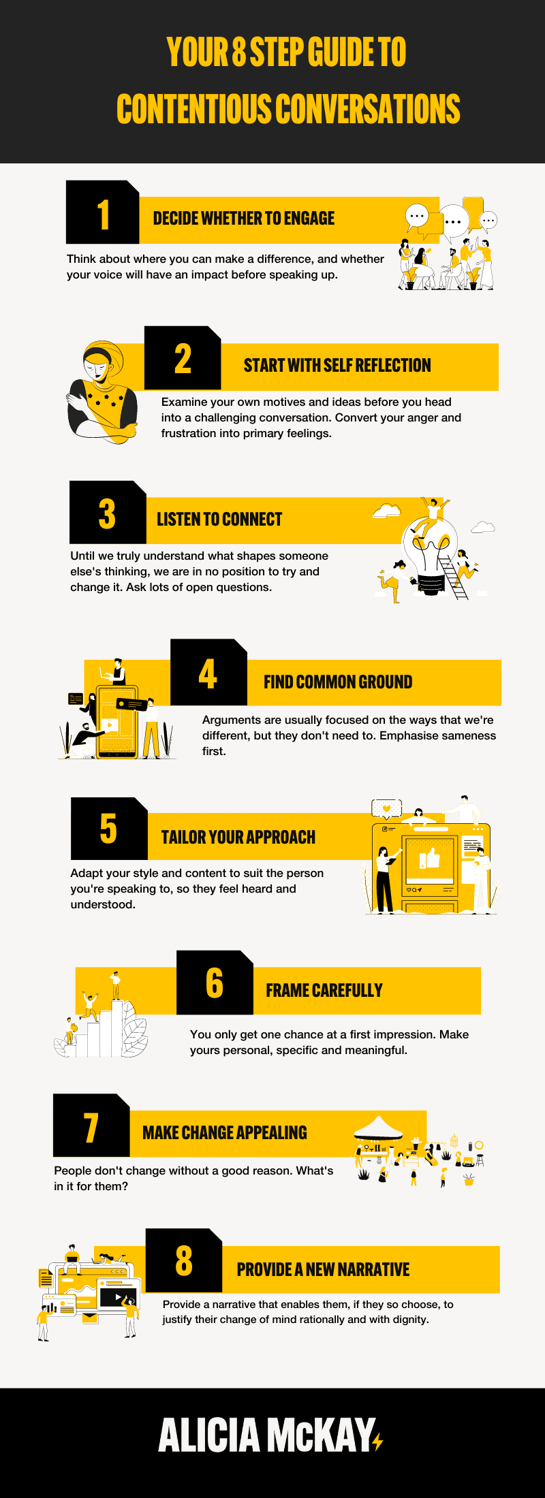

8 steps to having contentious conversations

- Decide whether to engage

- Start with self-reflection

- Listen to connect to their values and experiences

- Find common ground to start from

- Tailor your communication style

- Frame your argument carefully

- Make change appealing

- Provide a new narrative that leaves their dignity intact

1. Decide whether to engage

Before speaking up, think about where you can make a difference and whether your voice will have any impact. There is little value in expending emotional energy on people you don’t really care about.

Here are some prompts to help you decide whether or not you should engage in a challenging conversation or controversy:

-

Do you hold a position of power or influence in this conversation? If so, carefully consider what your engagement could or should look like.

-

Are people looking to you for a point of view? If so, it’s time to get ready.

-

Are you adequately informed? If not, get those Google fingers working at pace, or call a friend in the know.

-

Do you have a point of view or information that would bring understanding, support or a positive impact to this conversation?

-

Are you open and willing to learn?

-

What are the risks or consequences of not speaking up?

-

What are the potential harms of this conversation continuing unchecked?

-

Do you personally know the people involved?

-

Is there an opportunity to have this conversation privately?

-

Can you assume positive intent of the other person or people involved?

If you decide that you either could or should get involved, and you’re confident you can navigate the conditions, move ahead with the next steps.

2. Start with self-reflection

Examine your motives and ideas before you head into a challenging conversation. What are you hoping to achieve in this chat? How confident are you in your beliefs or ideas? Why are you so upset about this issue, and what is it bringing up for you? What feelings do you have? When did you first form your thinking, and is it still correct?

If you're angry, try to dig a layer deeper. Anger is a secondary emotion, which can only be met by anger. When you tap into the feeling underneath – sadness, disappointment, or guilt, for example, you have a better chance of connecting with the other person.

This is hard because primary emotions are more vulnerable and exposed, but those are emotions other humans are wired to connect with.

For example, you can create a path for connection with something contentious, like anger and frustration at the overturning of Roe v Wade. Tapping into primary emotions might lead to sentences like:

"I’m sad and disappointed for the vulnerable women left without a choice." or

"I'm scared my children won't be able to access the healthcare they need.”

These emotions are personal and specific but non-threatening and harder to take umbrage with.

3. Listen to connect

It’s hard to change the mind of someone we don’t understand. Until we know what shapes someone else's thinking, we are in no position to try and change it. Ask lots of open questions to help you understand where they're coming from.

Very few people are ignorant or inflammatory for fun (though it might look that way). Instead, everyone has genuine fears and concerns based on their personal values, experiences, and the information they've consumed.

One of the best memes I’ve seen recently is from The Workshop’s guide to COVID conversations that talk about “connecting, not correcting.” Connection needs to be the goal here before we even start to think about what it is that we want to say.

There are no hard and fast rules for this stage, as it largely depends on who you’re talking to and how well you know them. There’s a huge difference, for example, between talking to your spouse or best friend and talking to a colleague you don’t know very well.

The goal of connection is not to learn the details of their opinions or beliefs. Like anger, an opinion or point of view is a secondary device. Instead, we want to understand what lies underneath. Going deeper asks us to connect to two critical things—their values and their lived experience.

Connect to their values

In The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion, Jonathan Haidt argues that you can’t change people’s minds with rational explanations because we simply aren’t rational beings. We’re driven by underlying moral intuitions that we defend with reason later. These values and intuitions are so hard-wired or have been around so long that we often can’t see them.

Asking people why they hold their views, what's important to them, and when they first formed their opinions is a helpful way to unlock values. You might try reflecting your impression back—i.e., "It sounds as though you really value doing the right thing. Have I got that right?"—to ensure you understand.

“While you are actively learning about someone else, you’re passively teaching them something else. - Daryl Davis

Understand their experiences

You can’t argue someone out of an experience they’ve had—especially if you haven’t even given them the chance to tell you about it. By understanding when and how they formed their viewpoint, you’ll learn about what made them—and others like them—think this way.

When you understand the person or people you’re speaking to, you can adapt your reasoning or message to align with their values, fears and concerns.

Ask questions

In tricky conversations, it's tempting to jump straight to a response. As people speak and you hear the inaccuracies, inconsistencies and assumptions, your brain goes into overdrive, mentally preparing the list of things you can rebut.

Do. Not. Listen. To. This. Voice.

At least, not until you've responded with a question. For bonus points, try using a reflective questioning technique, such as Ask-Share-Ask. You ask a question, share what you heard, and then ask if there's anything they'd like to add and whether you got it right. This makes sure you have the right balance between listening and talking—it should be 2:1.

4. Find common ground

Arguments usually focus on how we're different, but they don't need to be. When we first connect and emphasise our sameness, we can see how other thoughts or beliefs might be relevant to us.

This asks us to find a place of commonality to start from. If you’ve done some self-reflection and taken the time to understand the other person, this won’t be hard to do. You’ll see what you can connect on, and that’s the place to start. Maybe it’s a shared value or similar experience. Maybe you are both passionate about fairness, loyal to your family or have a similar professional background. Starting from this place reminds you that you are conversation partners, not adversaries or targets.

The emotional connection ensures people feel safe and respected, freeing up bandwidth that might have been devoted to defending or attacking. When you demonstrate empathy and compassion for their point of view, they are free to engage with yours. Schieffer suggests using a “feel-felt-found” technique to frame this—i.e., “I know how you feel, I felt the same way, and what I found was…"

5. Tailor your approach

Adapt your style and content to suit the person you speak to so they feel heard and understood. I often work with engineers and elected local government members, who are generally unimpressed by fluffy ideas or corporate jargon. They have a strong bullsh*t detector, which I'm always aware of when presenting or facilitating. I use plain language, and strike to the core of what they think and value.

That means when I’m running strategic leadership sessions, I don’t wax lyrical about the power of innovation and the importance of vision. Instead, I suggest that by staying stuck in the operational details they have staff for, they’re operating below their pay grade or hamstringing their teams. This resonates because that’s not who they want to be. When I respect their expertise, work ethic, intelligence, and values, they listen.

Choose your style, then frame your position regarding their values and experiences, not yours. When we create arguments that speak to our moral frameworks, we can speak another language. Your position might make sense, but it's irrelevant if they don't share those ideas.

I saw this done well recently at a conference where a speaker spoke about access to housing. Appealing to a room of local government professionals, she didn't discuss social justice or human rights. Instead, she argued that housing should be viewed as “essential infrastructure” rather than a social good. The impact was immediate. By speaking in terms and ideas that resonated with her audience, she triggered an immediate change of perspective.

This argument allowed the audience to maintain their value system while embracing a new point of view.

6. Frame your argument carefully

You only get one chance at a first impression. It doesn't matter how clever your argument is if the first thing people hear sounds like an attack. They'll spend time mounting a defence while you speak rather than listening.

David Maxwell, author of Crucial Confrontations: Tools for Resolving Broken Promises, Violated Expectations and Bad Behaviour recommends the following formula to avoid unnecessary conflict or personal attacks.

-

Make it personal - Start from a place of personal values and use that to frame what’s coming next – ie “This is an issue of fairness for me, so I’m going to be quite strong in my opinion about this”

-

Make it specific. State the facts without generalisations. So instead of heading into “this is so typical of all men” or “you always…” or “you never…” use a description of the situation, e.g., “When I pointed out gender bias recently, it felt like my concerns were dismissed.”

-

Make it meaningful - Share the conclusion you drew from the facts, using I language – “I feel as though there’s a pattern of disadvantage here, and I’m wondering whether I’m safe in this environment.”

When we frame our arguments in these terms, we're not trying to present our ideas as facts. We've shared our context, experience and conclusions in a way that gives people an understanding of how we formed our thinking and owned our reality.

7. Make change appealing

“The only way to influence people is to talk about what they want and to show them how to get it.” - DALE CARNEGIE

People don't change without a good reason. Remember reactance, the physiological aversion to changing our minds? Change is scary and uncertain and often invokes loss - so make sure you link your thinking back to what's in it for them.

It's hard to move past that without a compelling benefit. To reach hearts and minds, provide the incentive for why it's worth thinking differently. Why should they buy into your way of thinking? What’s in it for them?

Tackle obvious barriers or defences – if you know the common arguments against your idea, don’t ignore them. Call them out and address them so they can't take up silent space in the conversation. If the people you’re talking to resist gender equality because it feels like reverse discrimination, have a gentle and open conversation about the myth of reverse discrimination and how it works. If people have valid concerns, addressing them doesn't make them more real; it makes them manageable. You can't work with what you can't see.

Above all, making change appealing to others isn't sleazy. It lets them know that you respect them, that they matter to you, and that you're trying to create something good, not make them look stupid.

8. Provide a new narrative

Provide a narrative that enables them, if they so choose, to justify their change of mind rationally and with dignity.

Remember, even though people think their ideas are grounded in rationality, they’re actually fuelled by emotions and values that have been post-rationalised. You can support that process by offering a new story to rationalise a change of mind.

The most important thing is that they have an opportunity to change their mind and keep their dignity and autonomy intact.

Here are a few ways to do that:

- Frame it personally – "I used to think, but then I learned." Or ‘I get that, although I was interested to see the evidence that…"

- Leave with class and compliments - "I really appreciate your openness to this conversation." "I love your approach to learning."

- Give them face-saving excuses – “We all used to think xx but now that we understand yy it looks as though zz is more correct/ fair”

Download the infographic with all 8 steps here:

Common questions and protests

These are all things that I think and need to wrestle with. Yours might be different.

Why should I be the bigger person?

You don’t have to be, but you can either be right or happy. If you’d rather be right, stay right. Your inclination either way may change from day to day.

You have the power, it’s your job to look after me.

This was hard for me to confront when I realised that people in power also had struggles and put their socks on one at a time. I recently spent time with the Youth Advisory Group at Oranga Tamariki, an incredible group of care-experienced youth advocating from inside the ministry. It was genuinely difficult to hear their pain and justifiable frustration and then go on to humanise the people who had let them down. I said something like, “I know, and you’re right. Also, these same people are doing their best. They’re frustrated, overworked, and going home to deal with their own battles – health, family, work, the lot. It sucks, but it’s true.”

Why should I minimise my outrage for your comfort?

You don’t have to—and sometimes, you shouldn’t. It depends on your goal. If you just need to be heard, preface your thoughts with that disclaimer: “I’m so frustrated and angry that I’m finding it hard to keep my anger in check, and the things I say next might reflect that.” That might give you the freedom to vent, but it may not contribute to progress—which might be OK. Make the judgment call depending on the conversation.

I’m tired of educating myself when I’m struggling with the impacts of incorrect beliefs.

Activist fatigue is real, especially when you’re personally affected by them. Set personal boundaries around when you engage. It’s not your job to be a full-time change champion. Sometimes, you can let it go and find an outlet elsewhere. Then, when you do choose to engage, you can do it from a better place.

You did wrong; I shouldn’t need to make you feel good while explaining it to you.

See the above points around being right or happy and setting boundaries. It’s not your job to educate everyone, and if talking to a specific person or group does you more harm than good, leave that work to someone better placed. You don’t need to fix everyone, and your pain is real. It’s OK if you’re too hurt to keep going.

Your thoughts

As I researched this article, I asked my mailing list and LinkedIn network for their thoughts, and I received an incredible outpouring of thoughts and ideas.

The clearest message I received was that many people are currently struggling with this and are feeling tired and fatigued by outrage. They want to have good conversations, but they feel like it's getting harder to do so. Here's some of the great input I received.

The only way to have these change making conversations is to earn their respect by acknowledging them and their fears. To hear them, tell them you hear them, and act like you hear them, then show them you heard them. – ANDREW MCKEOWN, EMAIL

Q: How do you talk to people with different opinions than you?

-

It depends on whom you’re talking to – the difference between a personal relationship/ spouse and a colleague.

-

Be kind. Approach people with compassion and try to understand them

-

Don’t rely on logic, if the belief is illogical. Instead, come from a place of values

-

Time – It takes time to change people’s minds; don’t expect an instant 180. Be happy to plant the seed.

-

Listen carefully. Ask questions to understand what’s behind the views.

-

Hold your views lightly – accept you might be wrong about thing

-

Earn the right to speak to them, earn their respect

-

Remember that you can’t control other people’s perspective or response

-

Online discussions go south too quickly - these conversations are best had in person

-

I need to find a balance between speaking and listening. If you don’t acknowledge the other side, you’re wasting your time and just as bad

-

Egos and fear get in the way – make sure your intentions are in the right place and you’re open to others

-

Always seek to understand first – if I was them, would I think the same?

-

It's OK to leave a conversation. Helen Walker suggests saying, “Hey, thanks for sharing your views, but I need to think about what's been said. Let's talk again soon. " This gives you time to process and understand your own triggers.

“If we all took responsibility for increasing our ability to listen deeply first, understand through the eyes of another and then develop an opinion/solution that does no harm, we would be heading in the right direction.” – LISA MITCHELL, LINKEDIN

Q: Where have you seen this done well?

-

Following a Te Ao Maori approach - entering into a powhiri or wananga and dealing with issues, keeping manaakitanga

Louis Theroux documentaries -

Harvard Business School's Program for Leadership Development and Black Swan Ltd

-

The Workshop is a Wellington-based research agency that supports people in having tricky conversations using simple tools like “Ask-Share-Ask,” which is weighted toward listening and connecting rather than telling. They put a lot of energy into understanding the big picture and history of issues and where individuals lie in that, focusing on the system rather than attacking people.

-

When you create an environment where everyone is valued and knows that their opinion is wanted and will count, while a decision may have to be made at some point

-

In the workplace,e it usually requires a truly independent facilitator—not a mediator—because it's about communicating to understand views, not changing others' minds.

-

Courageous Conversation Compass – knowing where we are personally, fully, and recognising all of the dimensions of others

-

Interest-Based Problem Solving - Karl Perry

-

(Many people said that they haven’t seen it done well!)

“Certainly not by our politicians, very rarely in fact. It’s not a strength that I see in humans. – ANON, EMAIL

Q: What mistakes do you or others often make?

-

Talking immediately without taking the space to think it through/ craft up your ideas first

-

Kiwis avoid conflict and miss opportunities to build understanding

-

Reacting emotionally and losing objectivity

-

Personal attacks

-

Body language

-

Taking it personally

-

Not being open to others’ ideas or life experiences

-

Speaking in absolutes (you always, you never…)

-

Being confrontational or forceful, which makes people retreat

-

Not staying respectful of the other person

-

Not listening properly, instead focusing on thinking up a response

-

Not knowing when to quit

-

Failing to be curious

-

Not opening-up

-

Not giving a f*ck

-

Becoming overwhelmed and walking away in frustration

-

Not able to empathise

-

Unconscious incompetence (We don’t know what we don’t know!)

-

Arguing from a point of authority, eg. Using religion with someone who is not necessarily religious.

“Very few people are 100% bad and very few positions are 100% wrong” – PHILIP HILL

Tips, questions and prompts

Karen Saunders offered the following helpful prompts:

- “Help me understand….”

- “I see where you are coming from” – acknowledging but not agreeing.

- “Thank you for that or direction. Are you aware of the impact? What are your thoughts on a way forward to address that?”

Brian Robb says:

-

Set the context and ground rules first - e.g. “I have been thinking about… and would like to know/understand your opinion/view on it (then give them time to provide their view without interjecting or arguing while remaining calm, especially if you disagree!). Ensure they know it is research and not an opportunity or challenge to try to convert each other to the other’s opinion.

-

Wait for an opportunity to reciprocate (listen first)

-

Look for common ground to acknowledge before going straight to difference

-

Use kindness; don’t be personal or combative

-

Be prepared to agree to disagree or pause.

Susannah Barthow on LinkedIn offered the following: "Asking questions is good. Reflect on why this is important to you. Is it the most important thing to spend energy on? What makes you feel strongly? Asking questions of the other person is good, too. For example, "Why do you think that?" Or "That's interesting. Can you tell me more?"

Clare Swallow on LinkedIn recommended picturing yourself in a different role: “I sometimes picture myself assuming the role of a reporter or a detective, leaving my bias at the door to understand their perspective. Asking questions with zero judgement and being interested in the response.”

I'd love your comments and thoughts on this one, too - go ahead and post them below!